People have introduced over 2,000 plants and animals to the UK. These non-native species are mostly harmless. However, around 10-15% of them spread and become invasive non-native species that harm the environment, the economy and our health.

Invasive non-native species come into the country either intentionally or accidentally, especially through travel and trade. The number of non-native invasive species is increasing every year.

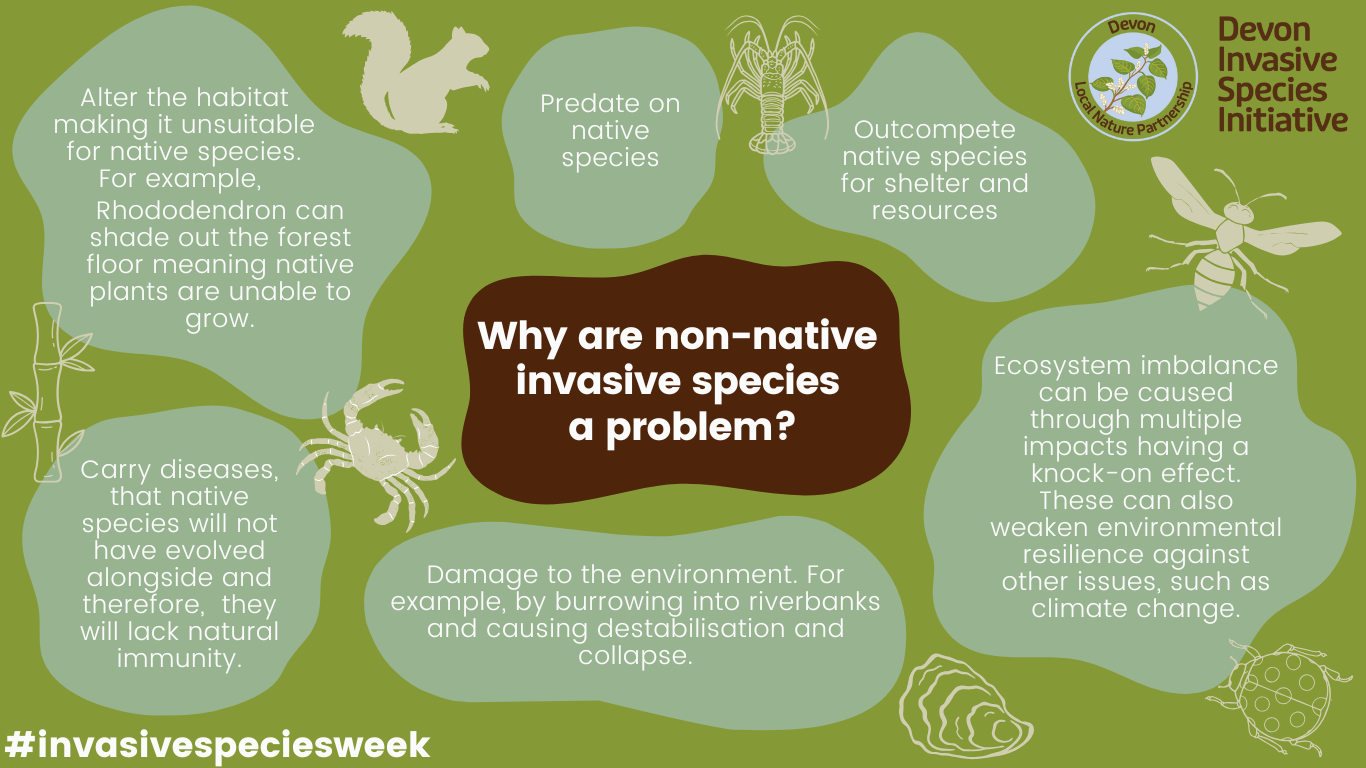

A 2023 study estimated that invasive non-native species (including fungi) cost the UK economy £4 billion annually. Some native species (such as bracken, Molinia and deer) can also become problematic and be invasive. Some impacts are highlighted in the diagram below.

A range of biosecurity measures can be carried out to prevent the risk of importing and spreading invasive non-native species. For aquatic species everyone is encouraged to follow the GB Non-Native Species Secretariat’s ‘Check, Clean, Dry’ procedure.

The Devon Invasive Species Initiative (DISI) has identified a list of Devon’s priority non-native invasive species. Those identified as Focus Species in need of urgent attention are discussed below, along with fungi.