This section focuses on the fish found in Devon’s rivers, lakes, small streams, canals, estuaries and other intertidalThe area of the shore that is covered by water at high tide and exposed to air at low tide. habitats.

Fish are an integral part of balanced healthy ecosystems. They feed on invertebrates and algae and provide food for birds (including kingfishers and herons), otters and larger fish. They are sensitive to pollution and changes in oxygen levels, temperatures and water flows and so are indicators of a healthy environment.

Many Devon communities have strong commercial fishing traditions and historically fish have provided both food and livelihoods. Freshwater fish still provide recreational opportunities such as angling, which generates revenue to local businesses, communities and the economy and can increase tourism.

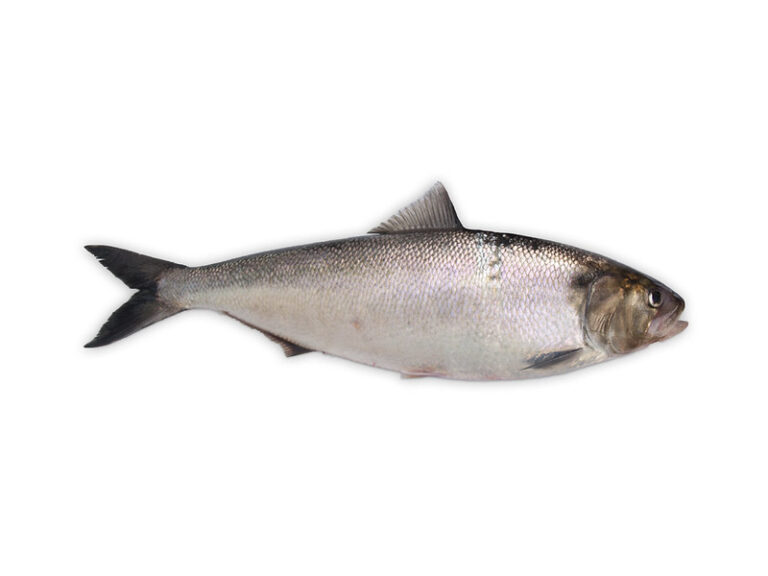

Some of Devon’s fish such as Bullhead, Bream, Stickleback and Chub live entirely in freshwater. Some such as Atlantic Salmon, Twaite and Allis Shad, Sea Trout, European Eel and Sea Lamprey have incredible lifecycles and migrate between the sea and our rivers. Others such as seahorses and the Tompot Blenny live in intertidal habitats.

Fish need healthy habitats to survive including:

- Clean, well-oxygenated spawning beds with suitable gravel. Most freshwater fish lay their eggs between the tiny gaps in gravel beds that provide oxygen and refuge for eggs and emerging fry and juvenile fish.

- An abundance and variety of food including invertebrates such as aquatic insects, crustaceans, and molluscs.