Clean air is vital for both people and nature.

Nitrogen

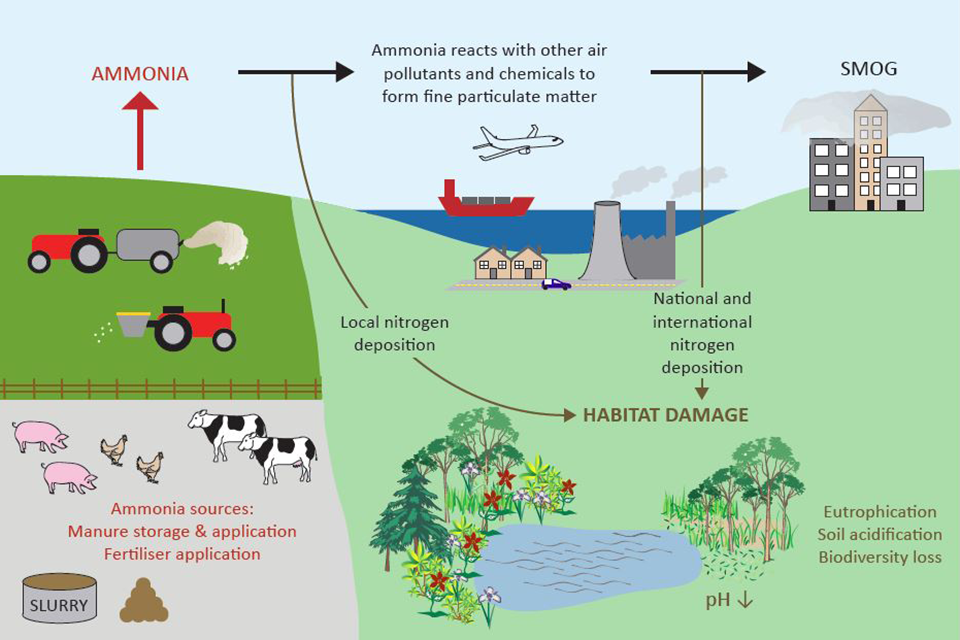

While many air pollutants exist, those containing reactive nitrogen are among the most widespread and damaging. Nitrogen pollution includes nitrogen oxides (NOx), mainly from combustion in transport and industry, and ammonia (NH₃), largely from livestock manure and fertiliser use. These pollutants travel as gases and particles through the air and can settle on habitats affecting biodiversity and ecosystem function through soil acidification, and nutrient enrichment of sensitive habitats.

Nitrogen pollution in Devon comes from many different sources. Agriculture produces the most emissions (ammonia) from practices such as intensive livestock housing, uncovered slurry stores, slurry and fertiliser spreading and high-input land management. Emissions (nitrogen oxides) from road traffic and burning fossil fuels add further pressure, creating localised hotspots near busy routes and in urban areas.

The environmental impacts of ammonia pollution. Image credit: Defra

Impacts on wildlife

Nitrogen pollution is a major driver of biodiversity loss in the UK and could impact the Government’s ambition to restore nature, as set out in the Environmental Improvement Plan 2025.

Many plant species in our wildlife habitats are unable to survive in these conditions leading to significant changes in vegetation and impacts on wildlife (especially invertebrates) which rely on these plants. Some species of mosses and lichens are especially vulnerable to nitrogen pollution and in turn so are habitats such as peat bogs (composed largely of bog mosses) and temperate rainforests (with rich lichen and moss communities). Read more in the drop downs below.

Impacts on human health

When inhaled, air pollution can also impact human health, contributing to respiratory illness, heart disease and other health problems. See the Air Quality Management Area drop down below.

Improving air quality

Improving air quality in Devon requires a focus on reducing nitrogen emissions and protecting sensitive habitats. Areas close to heathlands, bogs and other nitrogen-sensitive sites should be prioritised for emission reduction measures, land use change and habitat restoration and creation.

Habitats such as trees and woodlands act as natural filters, capturing airborne pollutants and reducing nitrogen deposition. Creating buffer zones by planting species-rich grasslands or hedgerows around farmland helps to intercept nutrients before they reach vulnerable ecosystems.

Farmers have a vital role in tackling nitrogen pollution. Adopting low-emission practices, such as improved manure management and precision fertiliser and slurry spreading techniques, can significantly cut ammonia emissions.

Nitrogen deposition in terrestrial ecosystems causes major changes in species composition, especially in nutrient-poor habitats. These areas often transition to species that thrive under high nitrogen availability, such as tall grasses, brambles and nettles, leading to less species richness and more plant growth. Sensitive lichens and bryophytes frequently decline or disappear, while nitrate leaching into soils becomes more pronounced. Soil acidification from nitrogen compounds further disrupts the ecosystem’s balance. Indirect effects include greater vulnerability of plants to frost, drought and pathogens, all of which impacts the species that depend on these habitats.

Under increased nitrogen, woodlands experience changes in the diversity and composition of lichens, fungi and ground flora. Semi-natural grasslands, which depend on low nutrient levels, often lose characteristic species when nitrogen inputs rise. Sand dunes can undergo significant species shifts and habitat loss.

High concentrations of ammonia cause direct damage to sensitive species, such as mosses. Heathlands and peat bogs are particularly vulnerable to high levels of ammonia, where it causes dramatic reductions in species diversity and changes flora, bryophyte and lichen communities.

Nitrogen oxides can also cause visible leaf damage and pose risks to mosses, liverworts and lichens that rely on atmospheric nutrients. Prolonged exposure leads to long-term changes in species composition across affected ecosystems.

Many of these species and habitats, along with others that are sensitive to nitrogen pollution, form the features of our important protected sites. Maintaining their integrity is essential for meeting conservation objectives and legal obligations. Public bodies have a statutory duty to ensure that activities within their remit do not compromise the condition of these protected sites. This includes considering air quality impacts in planning decisions and working collaboratively to reduce nitrogen emissions.

Habitat restoration

High nitrogen deposition and raised ammonia and nitrogen oxide concentrations can make it hard to restore habitats or create new ones. Excess nitrogen changes soil chemistry, favouring fast-growing species and reducing biodiversity. This nutrient imbalance can prevent the successful establishment of sensitive habitats such as heathlands, bogs and species-rich grasslands. These effects on plant communities in turn affect the wildlife species that depend on them. Therefore, it’s vital to address nitrogen pollution if we are to achieve long-term habitat and species recovery and meet nature recovery targets.

Air quality standards for ecosystems are expressed as critical levels (concentrations in air) and critical loads (amount deposited to land).

Critical levels: The concentration of pollutants (ammonia and nitrogen oxides) in the air above which damage can occur to ecosystems.

Critical loads: The amount of pollution (nitrogen) an environment can handle without causing harm to sensitive plants or ecosystems.

For nitrogen pollutants:

- Critical loads for nitrogen deposition can vary by habitat but generally fall within 5–15 kg of nitrogen per hectare per year for sensitive ecosystems such as heathlands and bogs.

- Critical levels of ammonia are typically 3 micrograms of pollutant per cubic metre (3 µg/m³) as an annual average for some vegetation (higher plants), with a lower threshold of 1 µg/m³ for sensitive species and habitats such as lichens and bryophytes. The critical level for nitrogen oxides is 30 µg/m³ for most vegetation types.

Many sensitive habitats in Devon already exceed critical nitrogen levels and loads.

To see a map of critical levels and loads see the Air Pollution Information System (APIS). Using the map controls, you can select specific pollutant layers, which will allow you to view information such as current ammonia concentrations for any area in Devon. The data shows that many areas in Devon are already exceeding critical loads and critical levels for pollutants, highlighting the urgent need to address this issue at scale.

The EA coordinates the UK Air Pollution Monitoring Network for Defra. As part of this the National Ammonia Monitoring Network (NAMN) provides gaseous ammonia concentrations (NH3) monthly at 113 sites. There are limited monitoring sites in Devon.

When considering human health, an Air Quality Management Area (AQMA) is a location where air pollution levels exceed national objectives. They are declared by local authorities under the Environment Act when monitoring shows legal limits are breached, mainly due to road traffic emissions. In Devon, several AQMAs have been declared including parts of Crediton, Newton Abbot and Cullompton. However the number of current monitoring stations is limited. For more details and an interactive map see Defra’s AQMA map.

Although nitrogen oxide emissions have fallen significantly in recent decades, ammonia levels in the UK have remained stubbornly high. Agriculture is responsible for around 88% of UK ammonia emissions: 48% from cattle, 27% from other livestock and 25% from non-manure fertilisers. Large livestock housing and heavily trafficked roads can create local “hotspots” of atmospheric nitrogen.

The UK has legally binding targets, as detailed within the Environmental Improvement Plan, to cut ammonia emissions by 16% and nitrogen oxides by 73% by 2030. Whilst this will bring improvements for nature, this will not be enough for nature restoration, and many sites will still exceed their environmental thresholds.

Ammonia emissions are expected to rise as the climate warms because higher temperatures increase the release of ammonia from manure and fertilisers. Longer growing seasons and changing agricultural practices further amplify this concerning trend.