Rocks

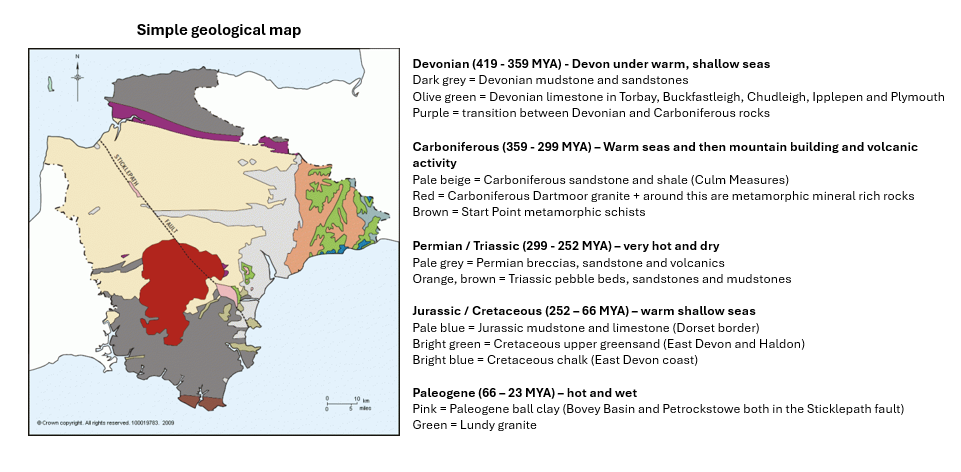

Devon’s landscape, soils and wildlife habitats are largely a reflection of our underlying and very varied geology. Devon’s rocks have been formed over millions of years through periods of sitting under warm shallow seas (shells and corals formed the Devonian limestone of Torbay and much later the Cretaceous chalk around Beer), mountain building and volcanoes (formed Dartmoor acidic granite) and hot dry deserts (formed the red sandstone of east Devon).

Rocks largely control the natural processes we find in any landscape, from the shape of the hills and valleys to the patterns of drainage and coastal erosion. Crucially, different rocks influence the development of different types of soils which in turn support different types of vegetation and wildlife habitat. You can see a simple map of Devon’s geology below.

This strategy does not include details relating to the conservation of geological sites. However, County Geological Sites are shown on the viewer (under Other Useful Layers) and you can see links to more information in Find out more below.

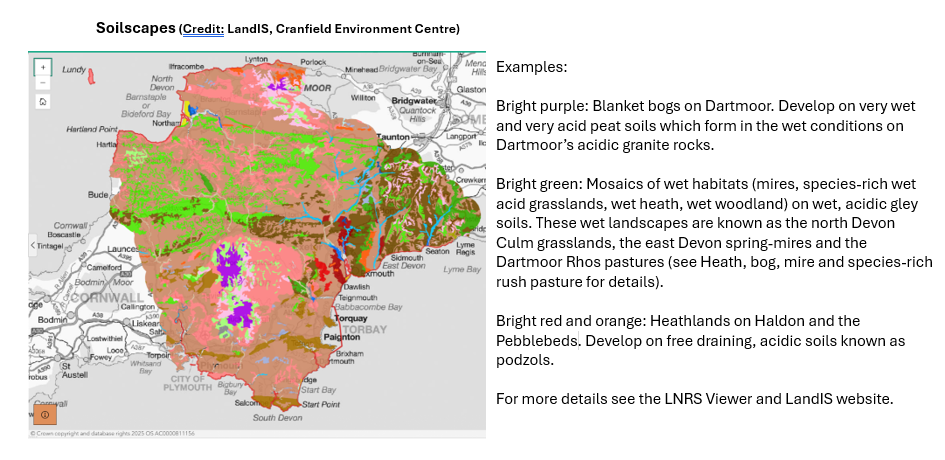

Slider: Devon’s geology, Soilscapes and soil habitat

Rocks and the features that they form (caves, cliffs, boulders and tors) are also valuable wildlife habitats that support many Devon Special SpeciesDevon Species of Conservation Concern which have been 'shortlisted' as needing particular action or attention. identified in this strategy. A few examples include:

- Limestone and chalk caves created in the Devonian limestone at Berry Head, Chudleigh and Buckfastleigh provide roosts for bats including Greater and Lesser Horseshoes. Caves in the Cretaceous chalk at Beer have both species of Horseshoe bats as well as the very rare Bechstein’s bat. The British Cave Shrimp lives in underground aquifers in caves and mines.

- Mines. The area around the edge of the Dartmoor granite is especially mineral rich (it’s known as the ‘metamorphic aureole’) and has a strong mining heritage. Many of these mines provide wildlife habitat, including for bats (there are large Greater Horseshoe roosts in the old Tavistock copper mines) and for rare lichens and mosses.

- Bare rock in natural cliff faces, man-made cuttings (railways, roads, towns) and quarries can provide unique wildlife habitats for plants, invertebrates and bird nesting sites. The large china clay quarries at Lee Moor and ball clay quarries in the Bovey Basin provide unique opportunities for wildlife with mosaics of ponds and seepages supporting Great Crested Newts and rare dragonflies such as the Scarce Blue-tailed Damselfly. Sand cliffs provide nesting sites for Sand Martins and areas of bare sand and clay provide habitat for bees, wasps and beetles.

- Granite tors and boulders (clitter fields) on Dartmoor support rare lichens as well as providing habitat for mosses and ferns and shelter for birds and invertebrates.

- Rare spiders live on screeA mass of small or loose stones lying on a slope or at the base of a hill or cliff. slopes on the upper Teign Valley gorge as well as on the cliffs around Start Point on the south coast.

Soils

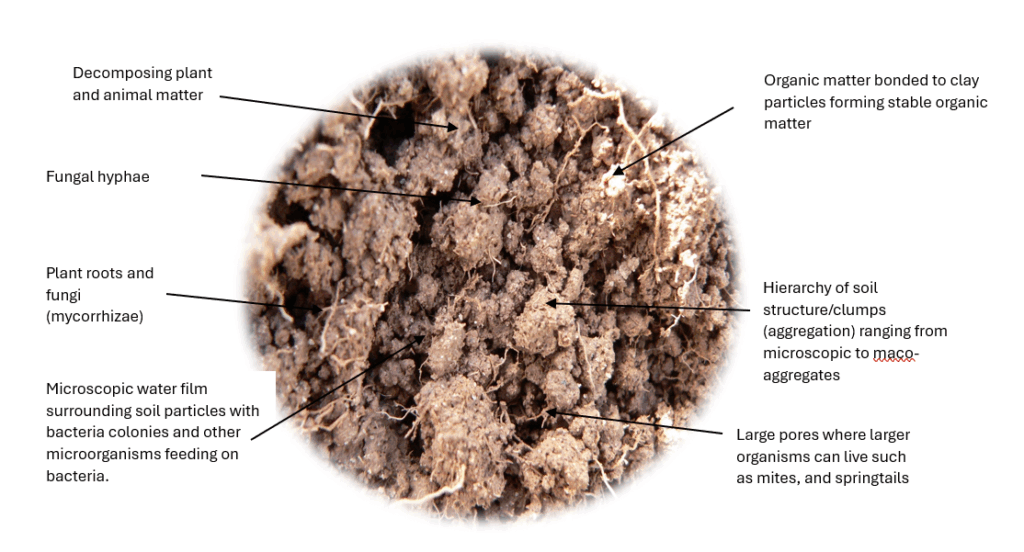

Soils are composed of clay, silt and sand from weathered rocks, pores full of air or water, dead and decaying vegetation and billions of tiny organisms. Different physical conditions create different soils over thousands of years (most of our soils are around 10,000 years old). Key things are the type of underlying rock, climate (wet or dry), landform (flat, steep, wet or dry) and vegetation. Soils are critically important to our lives and are an integral part of wildlife habitats. Soil functions help deliver our food production systems, store carbon, control flooding and water quality and recycle organic matter and nutrients. They also contain a vast and under-explored reservoir of biodiversity.

Over a quarter of all known species live in the soil, where they often go unnoticed. A few examples are earthworms, insect larvae, mites, springtails, nematodes, billions of bacteria, archaeaSingle-celled microorganisms that love harsh environments such as high temperature, very saline or very acid. Play an important role in nutrient cycles. and fungi. These organisms play a vital role in helping to form the soil structure. Soil particles have a film of water around them, which is where lots of microorganismsAn organism that can be seen only through a microscope. (bacteria and fungi) live and are preyed on by larger organisms. Earthworms, ants and other animals that move the soil such as moles, are known as earth engineers because their burrowing activity changes the structure of the soil. Earthworms ingest soil and produce casts which help to create new soil habitats. Diverse soil communities help to control outbreaks of pests and diseases by feeding on problem organisms.

Soils, Soilscapes and wildlife habitats

As Devon has such varied geology and landscapes we have lots of different types of soil. These soils all have different characteristics (wet and dry; acidic and calcareous) and so support different plant species, which in turn create different habitats. For example, thin, free-draining, calcareous soils have developed over the limestone rocks on the Torbay coast. These soils support lime-loving (rather than acid-loving) plants, which together form species-rich calcareous grasslands. In contrast, wet and acidic soils have developed over the clay shale rocks and mudstones of north Devon. Completely different plants thrive in these conditions, creating the wet Culm grasslands of north Devon.

Most of our free-draining, less acidic brown earth soils are now used for intensive agriculture, along with hedges, remnant woodlands and scattered species-rich grasslands. However, bats and birds feed on the earthworms, beetles and ants that live in the soils of arable and improved grassland fields for all, or part of, their lives.

Soils can be classified into a number of broad groups:

| Soil Group | Key characteristics |

| Brown earth soils | Freely-draining soils or with slight impeded drainage. Soils are slightly acidic, neutral or calcareous depending on parent material. They support woodlands and other woody habitats (orchards, wood pasture, parkland, scrub), species-rich lowland meadows and east Devon coast chalk grasslands. |

| Gley soils | Soils with long periods of seasonal waterlogging near the surface. Soils support mosaics of wet woodland, wet heath, mires and wet acid grasslands (Purple moor-grass and rush pastures). Soils can have peaty layers. |

| Podzolic soils | Very acid soils either freely-draining or with impeded drainage. Soils support mosaics of dry and wet heath and acid grasslands. Soil acidity and wetness form peaty layers. |

| Deep peat soils | Deep peat supports the bogs on Dartmoor and Exmoor. |

| Shallow soils | Thin soils over bedrock with varying acidity and drainage. Includes Torbay coastal limestones and sand dunes. Can be rich in mosses and lichens and provide important invertebrateAn animal that doesn't have a backbone, such as insects, spiders, worms, crabs and slugs. habitat, for example, bare areas for nesting bees. |

| Man-made soils | Soils found in urban areas, verges, gardens, old quarries and mine spoil heaps. They have huge potential for wildlife restoration and the creation of interesting plant communities. |

These broad groups consist of lots of different types of soil known as Soil Series. Soilscapes is a simplified national soils map that was produced to help show how different soils underpin different wildlife habitats (see the slider above). The Soilscapes have been used to help map the LNRS High Opportunity Areas for habitats (see the Mapping Methodology paper on the Mapping page). For more details on Soilscapes see the Soilscapes map on the LNRS Viewer (Other Useful Layers) and links in Find out more below.

For more details see a summary of the Devon Soil Groups and the LNRS overview of soils, geology and wildlife habitats, which sets out the relationship between geology, soils and habitats.